Sinking Mumbai's poor

In the megacity of dreams, survival of the poor often comes at the choice between death and debt.

Writer: Himani Naidu

Editor: Nihira

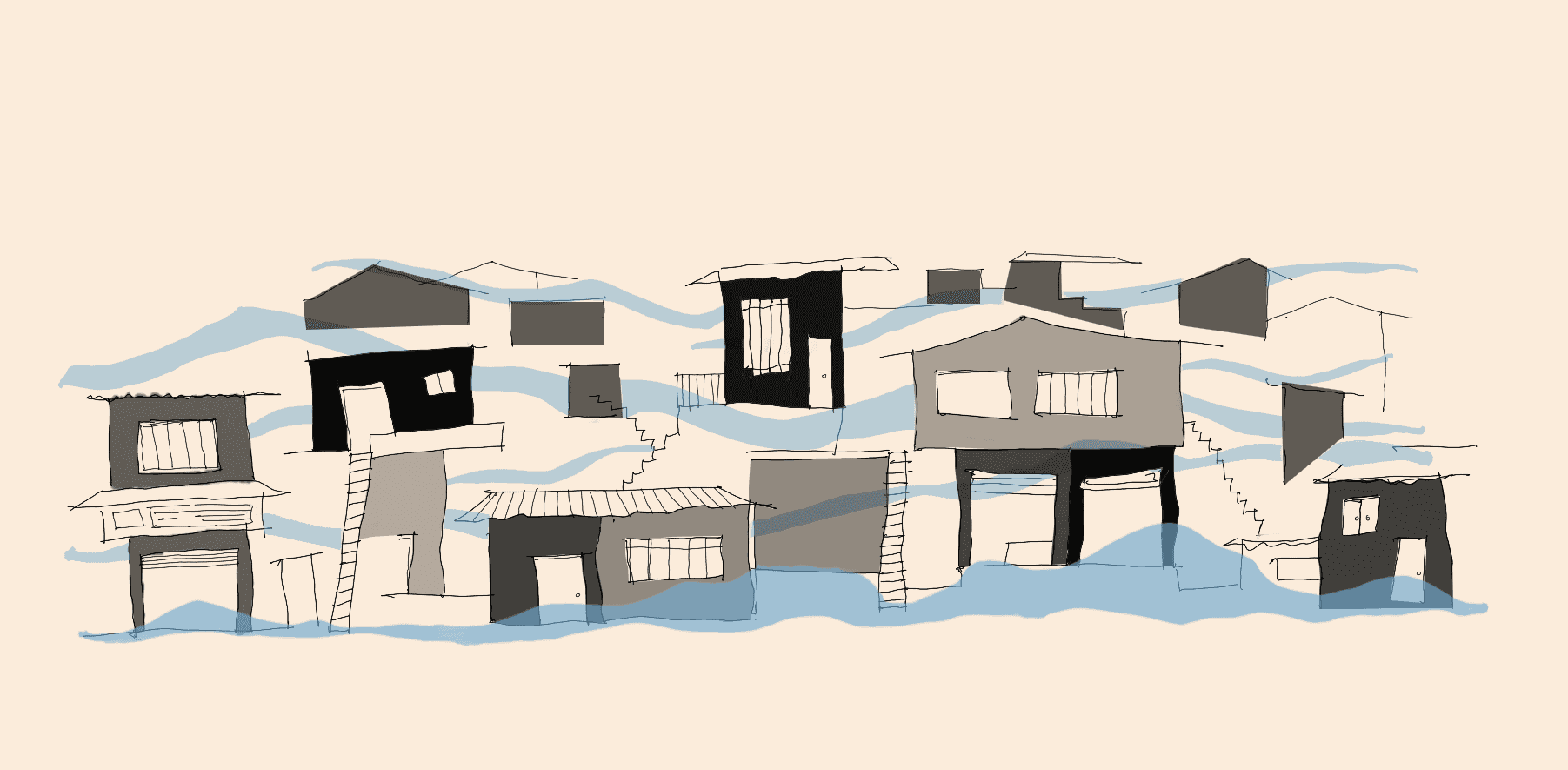

Illustration: Monsoons in Dharavi, Himani Naidu

-

Every year, Mumbai’s monsoons wreak havoc on Dharavi. Every year its residents appeal to the city’s civic body for help. Despite 2021’s torrential downpour claiming dozens of lives, they have received none.

In January, Amit (name changed) decided to build a plinth underneath his home which would raise it 3 feet higher, protecting it from flood damages. The Brihanmumbai Municipal Corporation (BMC) considers this illegal. A protective base ubiquitous almost everywhere around Mumbai has become a luxury for people residing in informal settlements. MMRDA or Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority’s citywide Development Control Regulations initiated two decades ago prohibit informal structures, like the one belonging to Amit, from exceeding the permissible height of 14 feet.

This regulation was imposed to supposedly curb slum growth and avoid construction of unsafe multiple storey buildings. In Mumbai’s anti-poor regime, however, the regulation fails to alleviate conditions in the slum it claims to protect. These legal constraints do not account for the needs of a growing population or of increasing migration to the area.

‘Aata aamhi karayncha tari kaaye? jagaayncha ki maraanchya?’

(‘What are we to do now? Do we live or die?’) exclaims Amit in dismay.

Tucked behind Sion Station, Patra Chawl is one of the oldest neighbourhoods in Dharavi. Amit has lived here his whole life. He claims the Chawl grew during the British era and walks me through its lanes, pointing out structures that were built more than 50 years ago. He shows me deep cracks running down walls of crumbling buildings. Gashed doors and windows now barely hang to their frames, having withered over time. Temporary fixes like salvaged metal sheets cover openings of undone structures held together by only a prayer. Some houses stand beyond repair. Amit mentions that these will eventually be demolished, leaving families homeless.

The unplanned nature of development in Dharavi has rendered people’s homes vulnerable to breakdown after even regular wear and tear. A plinth is the base that separates a building from the ground. It is a structural element that evenly distributes the weight of the house onto a wider plane. It protects structures from drainage or flood water along with insects and other creatures seeping in. This 3 feet of a marker which defines the foundation of a sturdy dwelling is missing in most of the area’s houses.

Annual flooding remains one of the major issues in Patra Chawl. Harshening rains have broken up and beaten down the homes of many. Every monsoon, houses are submerged in waters rising as high as 4 feet. This leaves families with no other option but to cram as many of their belongings as they can in the mezzanine built into their homes. More often than not, Dharavi’s residents have to seek temporary refuge with their neighbours living on upper floors. I saw open drains running throughout the settlement. Unfit to carry storm-water, these pipes get jammed and clogged. Amit mentions they were built around the same time as some buildings, half a century ago.

Noted historians Priyanka Srivastava, Sheetal Chhabria, and Prashant Kidambi have all expounded on the impact of British colonization on urban inequities that cut through the island till today. Srivastava writes in her recent book The Well-Being of the Labor Force in Colonial Bombay of mill workers- largely a migrant populace in colonial Bombay, “settled close to their mills in haphazardly constructed, dingy, overcrowded, undrained, and ill-ventilated chawls” which engendered several potential health issues. Since neither the government nor employers had any interest in providing workers with secure housing, labourers’ ‘homes’ were often unsafe constructions built for easy real estate profits and lacked integral infrastructural features such as “well-constructed sewage systems connected to a drainage network”.

Chhabria, in Making the Modern Slum – The Power of Capital in Colonial Bombay, shows how schemes enacted by Bombay’s City Improvement Trust led to landlords and property owners raising rents for tenants. This meant “laborers and seasonal migrants were priced out of housing and made compensatory choices to enter denser shared accommodations”. Their other option, as elaborated on by Kidambi in The Making of an Indian Metropolis was homelessness. Kidambi notes that “in the 1890s around 100,000 labourers usually slept on roads or footpaths”. He also points to the fact that housing was one of many conflicts in the urban poor’s concerns around well-being. Colonial Bombay was also plagued with severe water scarcity. These realities stand starkly in contrast with contemporaneous urban life in locales where European and upper-caste affluent natives resided.

Not much has changed since the 19th century. Even today, Dharavi’s residents are flooded at the same time they are parched. I talk to the women gathered around a shared tap, waiting for their turn to fill up water. Limited water supply has run the taps dry. It takes each woman several hours to fill up a few buckets. Savita says women are forced to sit by taps when they should be at work or taking care of their domestic chores.

Due to the prime location of the informal slum, Dharavi has suffered its share of politically motivated redevelopment plans that cater to everyone except its residents. Several promises have been made in the past but these are never followed through and remain electoral propaganda.

An article by the Indian Express mentions that a BMC survey conducted in October 2017 indicated there were approximately 90,500 hutments across Mumbai exceeding 14 feet. Amit says, in order to accommodate an ever-increasing floating population, many locals resort to illegally adding additional floors by paying almost five times the cost of construction to contractors. Apart from flooding, these structures are susceptible to catching fire and/or collapsing. In June, twelve people lost their lives after an unofficial building broke apart in Malad. The BMC has marked 407 buildings across the metropolis for immediate demolition.

In the megacity of dreams, survival of the poor often comes at the choice between death and debt.

Amit has been requesting BMC to grant him permission to construct the plinth for several months. He is yet to hear back. He fears that if he decides to go against the regulation and pay exorbitant amounts to local contractors, there still will not be any guarantee that his house remains safe from government-sanctioned demolition.

“The urgency of our requests is always lost in the bureaucratic process, where the decision never ends up favouring the poor”, he says.

Why is the urban working-class forced to waste hard-earned incomes for appeasing contractors? Why should they be extorted to keep their families safe, especially at a time when wages have decreased and poverty induced distress increased? Mumbai’s government focuses on a foggy future which keeps moving further away from the grim realities of the present. Narratives around Dharavi’s sporadic growth need to drastically change and focus on people instead of real estate interests or political actors.

Although a shift from direct violence of slum clearance drives, today’s redevelopment plans are still not aligned with the demands and aspirations of the city’s most vulnerable. This leaves Dharavi, and several other pockets like it, in disarray. Evicted in the middle of a pandemic last year, families living in Guru Tegh Bahadur Nagar after the Partition as refugees are still to be provided with liveable housing. According to Mid-Day, women like Harbachan Kaur and her four daughters were forced to move to “Kamothe, a remote location near Pavel, as they couldn’t afford rents of Rs 20,000 and hefty deposits” common in the city. Local commissioners have washed their hands of ensuring housing for the evicted by stating that “redevelopment does not come under their purview”. With little money to put food on the table, G. T. B. Nagar’s families are now expected to finance builders and contractors who will rebuild homes the city demolished. When public demolition axes live swiftly, why can’t public housing rebuild them?

Amit has returned to his old methods to survive water-logging by burrowing his family and essentials into the upper nooks of their home. He mentions the serious losses incurred by families. Water has already entered houses and damaged the flooring and furniture, among other things. Photos of the flooded chawl were duly sent to BMC officials, but the residents have yet to receive any response. As Mumbai prepares itself for the perils inseparable from lush rains, people will be asked to seek comfort inside their homes. But what happens when the government razes your home? Destitute Mumbaikars will be forced to manage without material support or feasible alternatives.

There are questions worth asking our administrators. Whose voice is heard in Mumbai? And whose is systemically drowned?