The caste of Indian fascism

The private life of tyranny is also its public architect. It is in the private sphere where fascism draws its daily breath. And in India, these breaths are regulated by the rhythms of caste.

Writer: Nihira

Editors: Kavya, Amshuman, Lakshmi

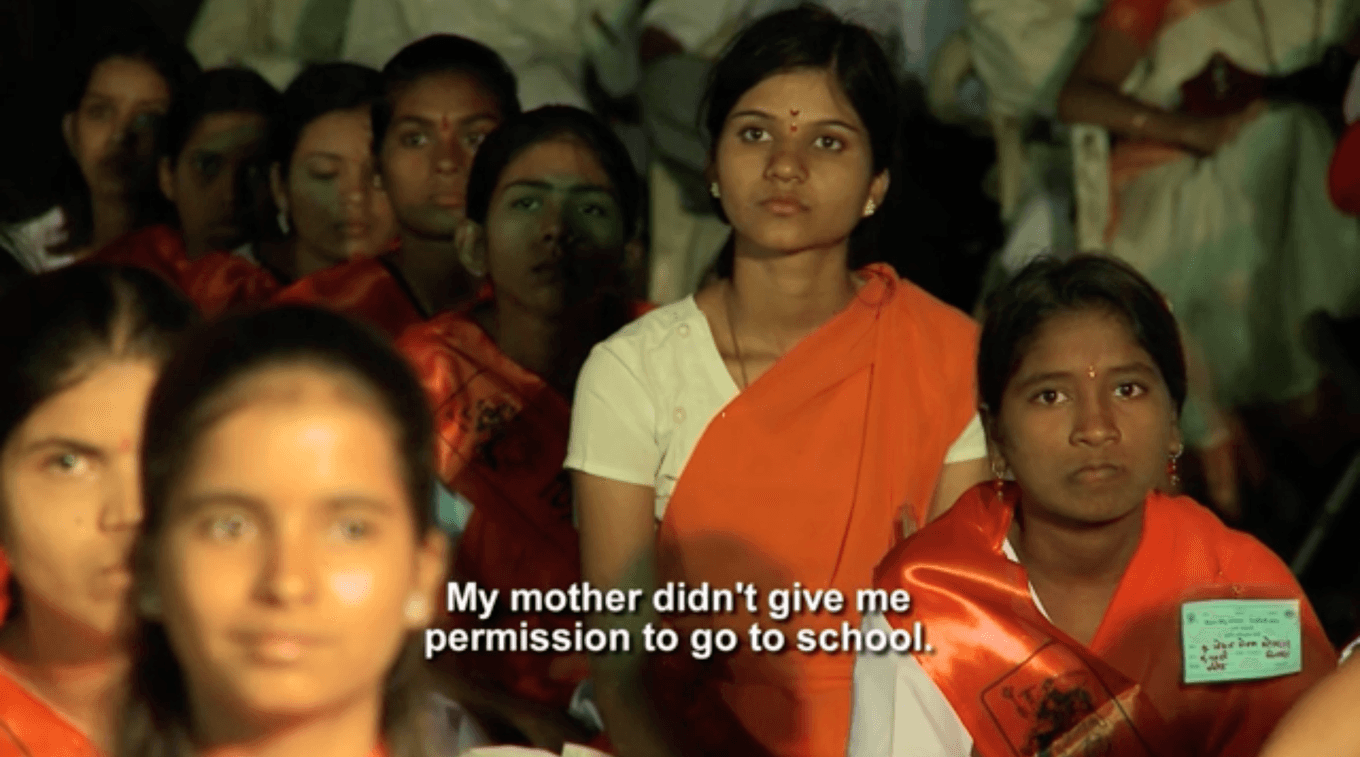

Still from:The World Before Her (Nisha Pahuja, 2011)

Orange flags blazed along lanes and buildings in the run-up to the ‘Ram Mandir’ inauguration. Some lit Muslim spaces on fire; even more lit oil lamps. All in celebration of what? The steroid-fuelled figure of Ram being inaugurated at the blood soaked temple in Ayodhya.

Before and since the temple’s grotesque ribbon-cutting on January 22nd, hoardings of Ram have been and continue to be installed on major and minor intersections in Bangalore. The day of the inauguration, by chance, I ended up on my scooter in one of the city’s by-lanes where a small group of Marwari women led a Jai Shree Ram march; genocide on their tongues, their children in tow. The way their saris were draped reminded me of the upper caste women in my mother’s hometown, hundreds of kilometres to the north. And the glee on their faces reminded me of the rot behind it.

What was this public march if not fascism? A march celebrating the pogrom against Muslims amidst Hindutva markings on government buildings, police stations and vehicles, corner shops, department stores, autorickshaws, trucks, tech parks, malls, public parks, bungalows, office buildings, apartments, swimming pools, hotels, electrical shops and hospitals. Nothing left untouched. Fascism everywhere. People write that Hindutva is rising. It was ‘rising’ before 1947. Today, it has ‘risen’. It reigns. To know how to kill it, we must know where it lives. Of course, on the streets, in the parliament, in jails and prisons, in the clinics, on the school playgrounds, in beef bans, in the stock markets, in hotel chains, in the conference rooms of the multi-nationals. But the private life of tyranny is also its public architect. The interior fascism of those women and children marching down the by-lanes of Bangalore is also what builds the exteriors of Hindu nationalism. It is in the private sphere where fascism draws its daily breath. And in India, these breaths are regulated by the rhythms of caste.

Last year, I attended the screening of documentarian Anand Patwardhan’s latest work, The World Is Family. A scene recorded more than a decade ago struck deep. Patwardhan speaks to a young Hindu boy in Ahmednagar, a small city in Maharashtra, who excitedly parrots his account of a riot that took place two days before Patwardhan arrival in the town. A town he travelled to explore the legacies of his uncle, Rau Patwardhan, a freedom fighter who organised sugar factory workers, and hosted the likes of Babasaheb Ambedkar. Standing before a plaque dedicated to Patwardhan’s uncle, the boy tells him how ‘Muslims started the riots’. At the veteran’s insistence that he spell out exactly what happened, the boy goes on to say that Muslims destroyed a Shiv Sena hoarding, which resulted in stone-pelting and rioting by the party’s supporters and other Hindu residents. Next to him, a younger Muslim boy, unknown to his peer, listens in silence. Patwardhan informs the viewer that the hoarding in question was of Maratha icon Shivaji Bhonsle dismembering Bijapur’s general, Afzal Khan. It had been intentionally placed in a Muslim settlement by the disturbingly more relevant than ever Marathi nationalist political party Shiv Sena (back then a unified body). This particular visual, Patwardhan says, has been used repeatedly in Maharashtra to provoke and incite Muslim sentiments. This distillation of the operating mechanism behind the violence did not reach that Hindu boy. Fascism had already made a home in him.

In 1991, Tanika Sarkar published an article called ‘The Woman as Communal Subject: Rashtrasevika Samiti and Ram Janmabhoomi Movement’ which is one of the more detailed accounts of the community labour undertaken by Hindu dominant caste women affiliated with the RSS and its many branches of Hindu nationalism. One of the women involved recounted to Sarkar how she trained her “two tiny children thoroughly in the daily sangh mantra recitations and cultivated proper ‘samskaras’ in them.” That boy in Ahmednagar too learnt his recitations somewhere. The article goes on to tell us:

“The samiti is then carried right into the heart of the domestic space and ceases to be an institution within the public sphere. […] One can see how useful such a loose and informal network would, [sic] have been to inculcate notions of ‘Hindutva’ and ‘Hindurashtra’ over a long period of time, and then, to swiftly link them up with a violent agitation which would find a ready support base without any direct and immediate organisational investment.”

Sarkar’s paper observes that samitis remain “silent” about caste and strategically avoid public discussion about it. But the logic of caste is received and imbibed by Hindus as an inaugural instruction. The private life of caste is what makes the material functioning of fascism that much more possible in India. How hard could it be to inculcate in children supremacy of Hindus, when they first learn about the supremacy of particular caste groups? If K Balagopal is right and caste is the “mode of reproduction of India’s ruling class“ (as Jairus Banaji succinctly summarises in his brilliant review of Balagopals’ works), then we must conduct a serious investigation into the class that has historically been the primary source of reproductive labour: women. If we want to idealise the notions of reproductive labour, we must be prepared to confront what horrors women as a class build in their reproduction of caste. It is not a coincidence that Narendra Modi in a campaign speech flagged Hindu women and told them they are at risk of having their ‘mangalsutra’ stolen by Congress, communists, and Muslims. The mangalsutra is the symbol of a Hindu woman’s material tie to her husband, his family, their caste, and their world. And it is important for the project of Indian fascism to indoctrinate in caste Hindu women that their mangalsutra, their world is being invaded.

The class of women is a complicated one to hold up when caste runs so definitely through it. We see glimpses of Sarkar’s study in Nisha Pahuja’s 2012 documentary ‘The World Before Her’. A fascinating parallel exploration of the arena of beauty pageantry and the women’s Hindu fascist group, Durga Vahini. In one scene, a field of young members of the group sit listening to a Vahini leader chastise them and warn them about the dangers of independence- and what she describes as ‘westernization’. While the film’s next scene connects this to the brutal violence men enact on women for independently seeking joy and fun (specifically women out drinking), it could very well be connected to the process of creating out of these women “foot soldiers of fascism”, what Balagopal otherwise calls lower middle-class Hindu men. These women are not just victims, they are capable of violence too. While we rightly focus on the Hindu men roving around and brutalising Dalits and Muslims on the streets, we must look at who the women in their lives are. There is a direct connection from this field of girls to that boy in Ahmednagar, or the 85-year-old woman in Jharkhand who vowed silence until ‘the Ram Temple is inaugurated’ (rather, until the desecration of the Babri Masjid is complete), or the school-going boys who joined in with their teacher—a Hindu woman—when she slapped a Muslim student. Hindu fascism lives in them all.

But, of course it is always the case that overtly violent groups like the Durga Vahini get more coverage than the everyday fascism that India thrives on. We can’t forget that it is the daily reproductive labour, much of which women contribute to, that goes into sustaining caste and religious divisions exemplified in groups like Durga Vahini. Ambedkarite educator and writer, Babytai Kamble, writes in her autobiography of how, as a child, she observed an elderly Brahmin woman shout abuses at her and other children and women from the Mahar community, while at the same time exploiting their labour as they collected and cleaned her firewood. The woman, housed behind “a chest-high platform, like a wall [built to] prohibit the Mahars from directly reaching the door”, proceeded to “throw from above, to avoid any contact, a couple of coins”. But this was preceded by an appeal to victimisation on the Brahmin woman’s part that were there to be any ‘problems’ with the firewood sticks, it would be her and her ‘pure house’ that would be ‘polluted’. An appeal that Kamble powerfully repudiates in the following passage:

“What a beastly thing this Hindu religion is! Let me tell you, it’s not prosperity and wealth that you enjoy—it is the very life blood of the Mahars! Mahar women’s sweat would have soaked the firewood. Sometimes when thorns pricked them, blood trickled and dripped on the sticks. Sometimes they cut their own limbs instead of the wood and blood poured down, drenching the wood with blood. Thus it was the very essence of the Mahar woman’s life that was found sticking to the wood. And yet the Brahmin woman objected to what they found sticking there!”

The performance of victimisation is swiftly paired with the enactment of violence. That is the dailiness of caste, the basis of fascism.

This is what has been building the Hindu nation. Many anti-caste thinkers and agitators like Jotiba Phule, Savitribai Phule, Fatima Sheikh, Babytai Kamble and Anoop Kumar have focused on education as a rallying force against the political economy of caste. The potency of this anti-caste knowledge was made clear when Delhi University removed the writings of the author Bama from its syllabus.

In a lecture for the leading institute on agrarian and rural research in India, Foundation for Agrarian Studies, Marxist historian Irfan Habib noted that Megasthenes, who lived roughly between 350–290 BC, mentioned the caste system during his first visit to Magadh. Habib also establishes the presence of caste in the Mughal period when land demarcation records retained the full names of higher caste individuals who had been granted land, but referred to lower caste grantees only through their sub-caste titles. But you might think caste has been a prosperous system if you browse the Central government’s new ‘Vedic Heritage Portal’ which includes lines like “ploughing is recorded [in the Vedas] as an auspicious mark of happiness” and verses that show “ploughmen tilling the land happily”. The portal states this “reminds [them] of the motto of Indian agricultural society ‘jay jawan jay kisan’”. How entangled land and war become in nation-states. But the site fails to indicate, for example, that according to the Atharva Veda itself, up to six or eight bullocks, owned by Vaishyas and pulled by Shudras, could be required to pull just one plough. Shudras who could not own the animals, the plough, the harvest, or the land would till and sweat and drag “happily”?

There is a straight line through history connecting the Atharva Veda, the Bhumihar-led Savarna Liberation Front and others like it active in early ‘90s Bihar, the systematic state persecution of Sikhs through the ‘80s, and preceding even that the mass murder of landless Dalit labourers in Keezhvenmani by landed Naidus and Thevars, the 2012 gunning down of 17 tribals by security forces in Chhattisgarh, and the Hindu Jat-Sangh nexus’ wreckage unleashed against Muslims in Uttar Pradesh’s Muzaffarnagar a year after, and everything that came prior, since, or is yet to come. That line is caste. And the women and children holding that line must be interrogated.

To argue this is not to underplay the violence upper caste Hindu women also experience. But it is to question how that is accompanied with the kind they themselves wield. Better writers have made explicit the linkages between caste, gender and capital in South Asia.1 Oppression does not erase the capacity to oppress. Experiencing violence does not remove the possibility to commit it.

Prachi Arya, like the Brahmin woman who abused Babytai Kamble and her mother, claimed victimisation of herself and ‘innocent Hindu children’ at the hands of ‘dangerous Muslims’ right before the carnage at Muzaffarnagar, and also remains protected by the police and justice system. It is the logic that allowed caste Hindu women like Anshu Sethi to kidnap and beat up a Muslim domestic worker in Noida. It is this logic that engineered vehicles like the Lorik Sena out of the historically oppressed Shudra sub-caste of Yadavs which, for a decade, committed atrocities against Dalit and tribal communities in its ‘fight’ against ‘Maoists’ using a name known in Bhojpuri folklore as the ‘Ahir’ love story that actually resisted Hindu kings and gods and Brahmanism2. In April of 1986, a village in Aurangabad saw Rajput men murder seven Yadavs. One can deduce that the Lorik Sena was not set up to counter this outgrowth of caste fascism. They claimed victimisation at the hands of those below them in the hierarchy who were asserting their own dignity, their own power. Just like caste Hindu women. Or the uncomfortable tale of Sunlight Sena in which wealthy Hindu Rajput and Muslim upper caste landlords found an ally in each other against the struggle waged by landless Dalits and lower-caste Muslims. Where were their mothers, wives, sisters, and daughters? What role did they play in maintaining such repressive alignments?

Progressives and liberals can believe, very similarly to their sangh counterparts, that Modi’s influence is a radical departure from the India of before. Sanghis argue that this is ‘good’, liberals contend it’s ‘bad’. But they seem to agree that there is a departure nonetheless. Liberals go so far as to believe that there once was a pristine India that was ’less unjust’ and ‘more tolerant’. Centuries-long evidence proves otherwise. The energy that many spend denouncing ‘today’s India’ as ‘unrecognisable’ is severely lacking when it comes to collectively organising towards the slicing away of caste and its tentacles. Even if its immediate reflections shift, the water that the ‘real India’ peeks through remains rotten.

There are specific challenges today that should of course be analysed and treated as such. For example, the passing of the Citizenship Amendment Act (2019) and setting up of prisons for migrants, refugees, and domestic residents (especially Muslims) signals a distinct material problem from what has come before which must be opposed with particular responses. But then the logic of a border itself is, perhaps, much older for a region that had them imposed on it and continues to impose it on regions like Kashmir. We must remember that although a specific issue demands a specific response today, it is also a reflection of structural violences. Fascism has risen on the back of caste. And the role of Hindu women and children, especially from dominant castes, should not go undiagnosed. They have ploughed their hands in the rotten water. These women who wield wooden sticks coated with the blood of another are slow to reckon with the fact that ‘India’ is a prison, and they will be nothing more than prisoners appointed as temporary wardens.

- In the landmark documentary Muzaffarnagar Baaqi Hai (2015), a Hindu man runs the filmmakers through names of homes owned by Muslims displaced by the riots, and Hindus who facilitated their displacement through force. While listing Hindu houses, he marks out the ones which were built in part or in full by the same Muslim masons who may never be able to return to their own homes.

- A version of Lorik’s folk-telling formed the basis of the first Sufi poem composed in Hindustani which dates to at least the 14th century and is attributed to Maulana Daud. The poem continues in oral circulation across the Bhojpuri world even today. It is also important to note that Yadavs are not a monolith, and there have existed Yadav dominant groups in Bhojpur and its surrounding areas like the Maoist Communist Centre which was aimed at abolishing caste oppression and which found solidarity with Dalit and Adivasi groups in the region.